doi: 10.62486/agmu202481

ORIGINAL

Interpretation of the imaginary of farmers about the products obtained through urban agriculture

Interpretación del imaginario de los agricultores sobre los productos obtenidos por medio de la agricultura urbana

María Angélica Vargas I1, Diego Armando

Osorio H1, Leonela Narváez G1, Verenice

Sánchez Castillo1 ![]() *

*

1Universidad de la Amazonia. Florencia, Caquetá, Colombia.

Cite as: Vargas I MA, Osorio H DA, Narváez G L, Sánchez Castillo V. Interpretation of the imaginary of farmers about the products obtained through urban agriculture. Multidisciplinar (Montevideo). 2024; 2:81. https://doi.org/10.62486/agmu202481

Submitted: 09-11-2023 Revised: 15-02-2024 Accepted: 06-08-2024 Published: 07-08-2024

Editor: Telmo Raúl

Aveiro-Róbalo ![]()

ABSTRACT

The present investigation was carried out with the objective of identifying the factors that affect the adoption of urban agriculture practices in the municipality of Florencia, Caquetá. To achieve this objective, an exploratory study was carried out that involved the collection and analysis of data through surveys and interviews with Mr. José. The result of this research was analyzed in detail on the interpretation of the farmers’ imaginary about the products obtained through urban agriculture, as well as recommendations to promote their adoption and improve their impact on the local population. So that is why urban agriculture is a useful tool to promote the sustainable development of cities. This is because it offers a viable solution to satisfy the growing demand for food and self-consumption in the urban area, discovering food sovereignty in addition to creating important social, economic and environmental benefits.

Keywords: Sovereignty; Self-Consumption; Urban Agriculture; Beneficial.

RESUMEN

La presente investigación se realizó con el objetivo de identificar los factores que inciden en la adopción de prácticas de agricultura urbana en el municipio de Florencia, Caquetá. Para lograr este objetivo, se llevó a cabo un estudio exploratorio que involucró la recopilación y análisis de datos a través de encuestas y entrevistas con el señor José. El resultado de esta investigación fue analizado de manera detallada sobre la interpretación del imaginario de los agricultores sobre los productos obtenidos por medio de la agricultura urbana, así como recomendaciones para fomentar su adopción y mejorar su impacto en la población local. A fin de que es por ello que la agricultura urbana es una herramienta útil para promover el desarrollo sostenible de las ciudades. Esto se debe a que ofrece una solución viable para satisfacer la creciente demanda de alimentos y el autoconsumo en el área urbana, generando una soberanía alimentaria además de crear importantes beneficios sociales, económicos y ambientales.

Palabras clave: Soberanía; Autoconsumo; Agricultura Urbana; Benéficos.

INTRODUCTION

In the 1960s and 1970s, the so-called Green Revolution emerged, which was believed to solve the problems of rice and wheat supply. This new trend brought “benefits” in using external inputs to cultivate the latest varieties. However, over time, the environmental damage and harm caused by this trend became apparent due to the indiscriminate use of synthetic chemical products, according to Pazos-Rojas A. et al. (2016).

“Massive production of crops, especially applied to monocultures of cereals such as corn and wheat. Under this proposal, several key components were implemented to make the idea feasible, including the use of improved varieties, the addition of high amounts of nitrogen fertilizers (e.g., urea, ammonium nitrate, ammonium chloride, among others), the implementation of irrigated plots, and the use of pesticides and herbicides. This resulted in very high crop yields, significantly reducing food costs and increasing availability. However, excessive exploitation of farmland has caused damage to the environment and the members of the community.” (p7).

Faced with this problem, which affects us due to the aforementioned consequences of this guideline, urban agriculture emerges as a solution. In conceptual terms, the FAO (2015), cited by Ángel-Lozano and Nava-Tablada (2019), defines urban and peri-urban agriculture (UPA) as the cultivation of plants (mainly with short production cycles) and the raising of animals in and around cities to meet the food needs of the urban population.

At the national level in Colombia, specifically in the cities of Bogotá, Medellín, and Cartagena, the Bogotá and Medellín Botanical Gardens and international institutions have trained more than 50 000 people in techniques for growing crops in urban spaces. “In Medellín, there are 7 500 gardens in 90 municipalities. These are complementary initiatives to the existing MANA10 Plan and Bogotá sin hambre (Bogotá without hunger)” (Zaar M, 2011, p. 2-3).

At the local level, during the administration of then-President of the Republic of Colombia Juan Manuel Santos Calderón, peace talks began with the now-defunct FARC-EP guerrilla group. One of the crucial points agreed upon in these talks was comprehensive agrarian reform and the reintegration of former combatants into civilian life with government support. For this reason, and in compliance with the agreements, the municipal government of Florencia, Caquetá, launched the Urban Agriculture program. The municipal government of Florencia-Caquetá launched the Urban Agriculture program to heal the wounds of “violence.” This initiative has benefited more than 3,000 people, 55% of whom are women. The process is supported by the UN World Food Programme (WFP) in coordination with the Unit for Comprehensive Care and Reparation for Victims (UARIV) and the Caquetá Regional SENA. Therefore, this research aims to analyze and understand the factors that influence the adoption of urban agriculture practices in the municipality of Florencia, Caquetá. The interpretation of farmers’ perceptions of the products obtained through urban agriculture was analyzed.

METHOD

This research was conducted in the municipality of Florencia, Caquetá, located in southern Colombia, in the Amazon region, at coordinates 1°36´51“north latitude and 75°36´42” west longitude, with an average altitude of 242 meters above sea level, average annual precipitation of 3 840 mm, and temperatures ranging between 25°C and 35°C. (Patiño et al., 2016).

This research is based on or shares the hermeneutic historical paradigm, as it seeks to identify the factors that influence the adoption of urban agriculture, as well as the motivations of families to engage in this type of production. This activity is intrinsic to everyday urban life and an active means of livelihood within the productive activities of families (Santos Rivera, 2010). However, Chilean sociologist Manuel A. Baeza suggests that hermeneutics allows for a different positioning concerning reality: “that of latent meanings” (2002, cited in Cárcamo, 2005, p.204). He also proposes that the hermeneutic researcher empathically assumes the subjectivity of the text (or of the various readings), including their prejudices.

An in-depth interview was conducted based on the perceptions of the producer, José. The interview was conducted in person at the home where he carries out his urban agriculture activities. The information obtained from the producer was thanks to the compilation of hours of informal recordings and direct interviews, which were transcribed in Word and entered into the qualitative data processing software Atlas Ti, version 9.0. Subsequently, the findings were written up, and the respective triangulation was carried out.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

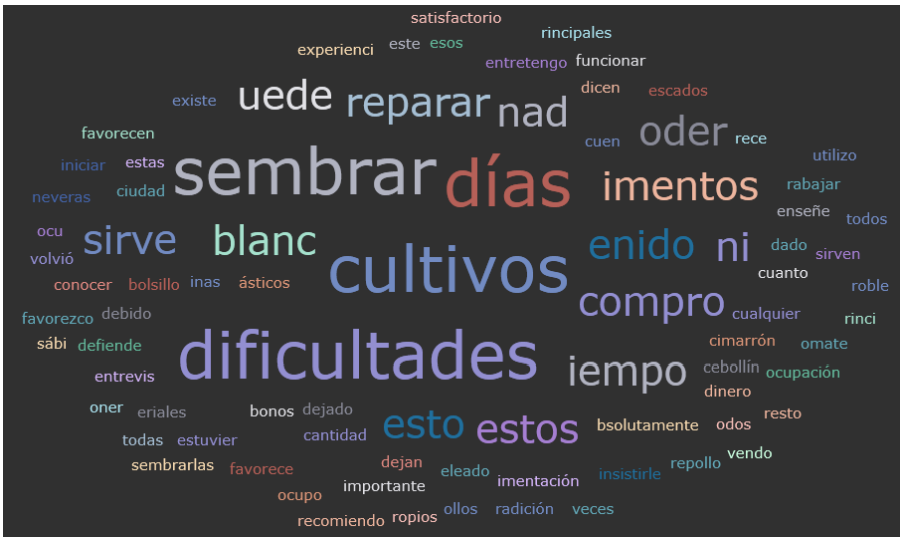

Exploratory analysis – word cloud

Within the perception of urban agriculture, many points of view or arguments were discovered that lead to what it is and how it works, within the perception of Mr. José from the city of Florencia in the Tymi neighborhood. He believes that urban agriculture is linked to the need to counteract the rising cost of daily life of the available food. Within his perception, words such as “crops,” “soil,” “fertilizer,” and “seeds” stand out. “dedication,” ‘benefits,’ and ‘difficulties.’ This results in a more straightforward and more flexible approach, as it does not require large tracts of land, but rather a dedication and a love for what one does, as Mr. José affirms: ‘They say that the land is useless, but it is the person who is useless’ (Figure 1).

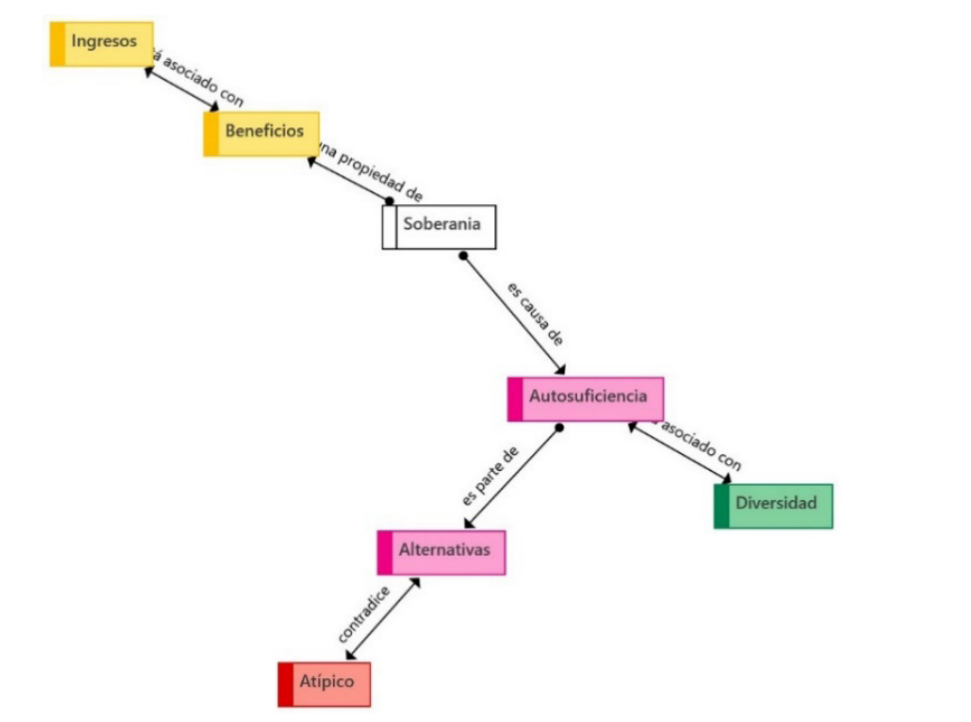

Deductive analysis – family network

Globalization has permeated the food and production customs and traditions of millions of families in rural and urban areas. As a result, there is growing concern about producing for sale and commercialization, with little importance given to self-consumption. However, some experiences counter this dynamic, developing crops and processes that promote food autonomy and sovereignty. It was therefore necessary to identify the perceptions of these farmers in urban areas, which make them different cases worthy of replication.

In this vein, interviews with urban farmers in the city of Florence identified three categories of analysis: economic-productive, technical, and perception.

Figure 1. Word cloud: perception of urban agriculture

Economic-productive category

According to Correa (2023), economic production refers to any activity involving producing goods and services for sale. These include agriculture, industry, manufacturing, commerce, mining, energy, etc.

For the interviewee, economic progress should be understood from the perspective of self-sufficiency and food sovereignty, not only production for the market. For him, food sovereignty is the central axis for the sustainability of each family and, in this way, achieving self-sufficiency and economic balance. This statement coincides with that of García (2013), who argues that sovereignty refers to the ability of a community, region, or nation to determine its food systems rather than relying on external systems to meet its food needs.

However, to be self-sufficient, it is necessary to promote diversity, that is, more products, better food, more excellent income opportunities, and therefore greater sovereignty. In this context, diversity means recognizing and respecting the variety of ways communities produce, distribute, consume, and share food and the cultural, social, environmental, economic, and nutritional value of these practices (Domínguez et al., 2022).

Therefore, sovereignty generates social and economic benefits since surplus generation provides sporadic income for families and self-sufficiency, favoring savings on purchasing food outside the system. This situation in the urban context is considered atypical, given that culturally, food production and self-sufficiency are concepts associated with rural life (figure 2):

Figure 2. Economic-productive family network

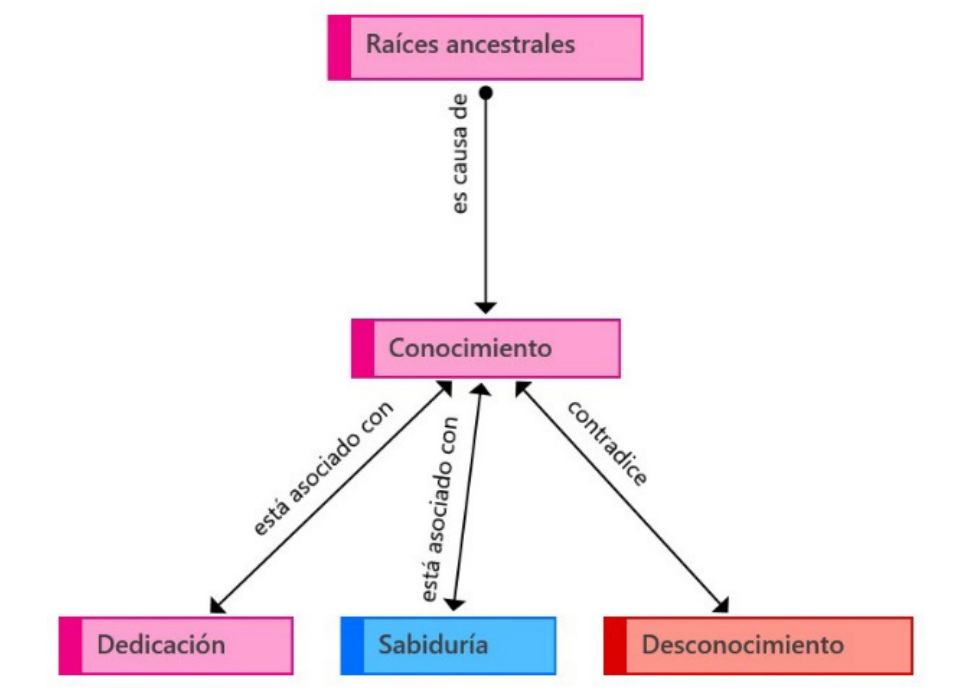

Technical-production family

The production technician for the study of urban agriculture is an essential tool for understanding the factors that influence agricultural production in urban areas. According to Ngozi (2019), the production technician is a professional based on knowledge acquired empirically or inherited from their ancestral roots in different skills for maintaining and improving other crops in urban spaces. These include communal plots, terraces, community gardens, rooftops, nurseries, and rainwater harvesting systems.

As mentioned by Méndez et al. (2005), the phenomenon of urban agriculture, from its different angles, breaks down the ignorance of the exclusive association between agriculture and rurality, opening up the possibility of integrating agricultural activity into urban life, which is generally characterized by the unproductive use of land and the predominance of an industrial-transforming lifestyle. Thus, to the extent that it is said that the rural is not currently limited to agriculture, it is equally worthwhile to look at its usual counterpart, arriving, if necessary, at the following conclusion: today, the urban includes direct agricultural and livestock production.

This explains the success of Mr. José’s various crops, which, as he describes, requires not only enthusiasm and patience but also a serious commitment to understanding the technical aspects of agriculture for sustainable practices (DOWEL, 2018), as well as the wisdom acquired through daily experience in his productive activity.

Figure 3. Technical-production family network

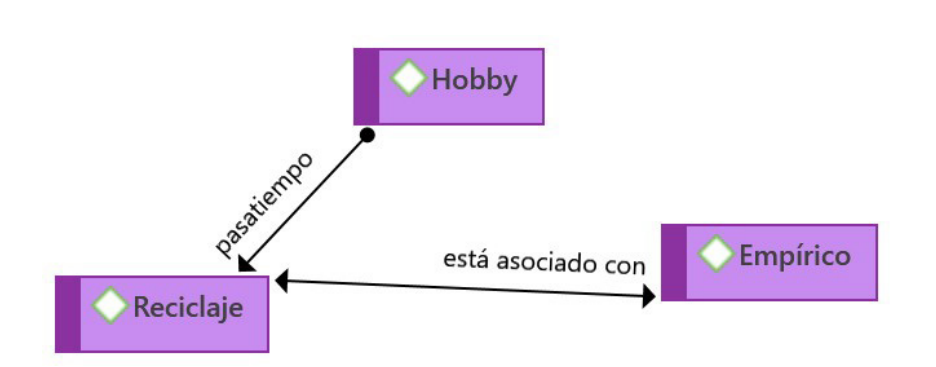

Perception Family

According to (Reeve et al., 2020), perception is the process by which our complex sensory system receives information from the environment, interprets it, and uses it to understand the world around us. Based on this statement, it is understandable why some people view agriculture as a hobby rather than a necessity or a job. Adopting recycling strategies, such as reusing used materials, has become a common practice to reduce waste production and mitigate the effects on environmental quality (Borsani, 2011). Based on the above, we note how some elements (non-renewable), such as tires, are used to support the various substrates for planting different crops. All these adaptation, implementation, and control processes have been developed empirically, obtaining favorable results in the process.

Figure 4. Family network Perception

CONCLUSIONS

We often want to find solutions to economic problems and rising food prices outside our homes, so urban agriculture is a valuable tool for promoting sustainable urban development. This is because it offers a viable solution to meet the growing demand for food in urban areas and creates significant social, economic, and environmental benefits. This has led to a new perception of agriculture (urban agriculture). Let us focus our efforts on growing our food in a controlled manner in small spaces with dedication and effort. In that case, we will see the welcome results of breaking away from the inflationary phenomenon of basic household products since, regardless of soil conditions, we can grow and produce our food and thus save money compared to products purchased at the market.

REFERENCES

1. Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional para el Desarrollo [AECID]. (2018). Seguridad alimentaria y nutricional en la cooperación española: pasado, presente y futuro.

2. Ángel-Lozano, G., & Nava-Tablada, M. E. (2019). Limitantes técnico-productivas y socioeconómicas para la adopción de la agricultura urbana. El caso de la red de agricultura urbana y periurbana de Xalapa, Veracruz. Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems, 22, p. 97-106.

3. Bocchi, C. P., de Souza Magalhães, É., Rahal, L., Gentil, P., & de Sá Gonçalves, R. (2019). A década da nutrição, a política de segurança alimentar e nutricional e as compras públicas da agricultura familiar no Brasil. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública, 43(Supl. 1). https://doi.org/10.26633/rpsp.2019.84

4. Bonet de Viola, A. M., Vidal, E. A., Piva, E., Saidler, S., Schierano, V., & del Pazo, M. (2021). La primacía de los derechos sociales relacionados con un nivel de vida adecuado: una reivindicación (in)esperada de la pandemia. Revista de La Facultad de Derecho y Ciencias Políticas, 51(134),p. 83-99.

5. Borbón-Mórale, C., Robles Valencia, A., & Huesca Reynoso, L. (2010). Caracterización de los patrones alimentarios para los hogares en México y Sonora, 2005-2006. Estudios Fronterizos, 11(21), p.203-237. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-8842(82)90011-6

6. Borsani, M. S. (2011). Materiales ecológicos: estrategias, alcance y aplicación de los materiales ecológicos como generadores de hábitats urbanos sostenibles.

7. Botía-Rodríguez, I., Cardona-Arguello, G. A., & Carvajal-Suárez, L. (2019). Patrón de consumo de verduras en una población infantil de Pamplona: Estudio Cualitativo. Universidad y Salud, 22(1), p.84 - 90. https://doi.org/10.22267/rus.202201.178

8. Buitrago-Guillen, M. E., Ospina-Daza, L. A., & Narváez-Solarte, W. (2018). Silvopastoral systems: An alternative in the mitigation and adaptation of bovine production to climate change. Boletín Científico Del Centro de Museos, 22(1),p. 31–42. https://doi.org/10.17151/bccm.2018.22.1.2

9. Cárcamo V., Héctor. (2005). Hermenéutica y análisis cualitativo. En: Revista de epistemología de las ciencias sociales Cinta de Moebio (23), p. 204-216, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile. En: http://www.facso.uchile.cl/publicaciones/moebio/23/carcamo.htm

10. Correa, F. (2023). Economía, ecología y democracia: Hacia un nuevo modelo de desarrollo. Editorial Catalonia

11. Diccionario de la lengua española [RAE]. (2019). Adopción. Adopción. https://dle.rae.es/adopción

12. Domínguez Ruiz, Y., & Soler Nariño, O. (2022). Seguridad alimentaria familiar: apuntes sociológicos para lograr sistemas alimentarios locales inclusivos, municipio Santiago de Cuba. Revista Universidad y Sociedad, 14(2), 446-457.

13. Ekmeiro Salvador, J., Moreno Rojas, R., García Lorenzo, M., & Cámara Martos, F. (2015). Food consumption pattern at a family level of urban areas of Anzoátegui, Venezuela. Nutrición Hospitalaria, 32(4), p. 1758–1765. https://doi.org/10.3305/nh.2015.32.4.9404

14. Ester Casanova, Blasi Urgell Morales, Josep Mª Urgell Blanch (2013). Manual de iniciación al huerto urbano. http://media.firabcn.es/content/S112014/docs/Manual_iniciacion_huerto_urbano.pdf

15. Franco-Crespo, C., Andrade-Sánchez, V., & Baldeón-Báez, S. (2021). Identificación de modelos de producción sostenible de alimentos en el cantón Píllaro como aporte a la soberanía alimentaria

16. García, A. (2013). La Soberanía Alimentaria: Concepto y Desarrollo. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas, 4(2), 355-369.

17. García-Nieto, M.T., Viñarás-Abad, M., & Cabezuelo-Lorenzo, F. (2020). Medio siglo de evolución del concepto de Relaciones Públicas (1970-2020). Artículo de revisión. El Profesional de La Información, 29(3), p.1 -- 11. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.may.19

18. Huerta, S, K. K., & Martínez, C, A. L. (2018). La revolución verde. 4(c), 1040–1052.

19. Ibarra, J. T., Caviedes, J., Barreau, A., & Pessa, N. (2019). Huertas familiares y comunitarias: En Huertas Familiares Comunitarias (p. 17–28).

20. Ingram, J. (2020). Nutrition security is more than food security. Nature Food, 1(1),p. 2. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-019-0002-4

21. López-González, J. L., Álvarez-Gaxiola, J. F., Rappo-Miguez, S. E., Damian-Huato, M. N., Méndez-Espinosa, J. A., & Paredes-Sánchez, J. A. (2019). Family Gardens and Food Security: the Case of the Municipality of Calpan, Puebla, México. Agricultura Sociedad Y Desarrollo, 16(3), p. 351–371.

22. Martínez, R., Trejo, G., López, M., & Velázquez, R. (2018). Estudio de las organizaciones y su entorno regional. Oaxaca en la sustentabilidad.

23. Méndez, M., Ramírez, L., & Alzate, A. (2005). La práctica de la agricultura urbana como expresión de emergencia de nuevas ruralidades: reflexiones en torno a la evidencia empírica. Cuadernos de desarrollo rural, (55), 51-70.

24. Mirafuentes, C., & Rosa, D. (2019). La Revolución Verde y la soberanía alimentaria como contrapropuesta.

25. Morán, A, N., & Hernández, A, A. (2011). Historia de los huertos urbanos. De los huertos para los pobres a los programas de agricultura urbana ecológica. https://oa.upm.es/12201/1/INVE_MEM_2011_96634.pdf

26. Nadal, A., Cerón, I., Cuerva, C, E., Gabarrell, D, X., García-Tornel, J, A., Pons, V, O., & Sanyé-Mengual, E. (2015). Agricultura urbana en el marco de urbanismo sostenible. Temes de disseny, (31), p.92-103.

27. Ochvano, B. (2020). Factores que determinan la adopción de tecnologías orgánicas por los productores de cacao (Theobroma cacao L) del Distrito de Irazola - Provincia de Padre Abad - Ucayali - Perú. p. 34–47.

28. Oficina del Alto Comisionado para los Derechos Humanos [ACNUDH]. (2020). Declaración universal sobre la erradicación del hambre y la malnutrición. https://www.ohchr.org/SP/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/EradicationOfHungerAndMalnutrition.aspx

29. Olguita Lucía Parra Saldaña (2018, 27 de noviembre). Agricultura urbana

30. Pazos-Rojas, L. A., Marín-Cevada, V., Elizabeth, Y., García, M., & Baez, A. (2016). Uso de microorganismos benéficos para reducir los daños causados por la revolución verde. Revista Iberoamericana de Ciencias, 3(7),p. 72-85

31. Reeve, J., Olson, J. E., & Walsh, A. J. (2020). Psicología. México: McGraw-Hill Interamericana.

32. Referencia: Ngozi, J. (2019). Técnico Productivo en Agricultura Urbana. El diamante en el agro. Recuperado de http://www.eldiamanteenelagro.com/como-ser-un-tecnico-productor-en-agricultura-urbana/.

33. Ricardo, R., C, M, & GIL, Z, M. L. (2019). Huertas urbanas como alternativa de desarrollo económico sostenible. Universidad Nacional abierta y a distancia - UNAD. Especialización en gestión de proyectos.

34. Ruiz Agudelo, C. A., Hurtado Bustos, S. L., Carrillo Cortes, Y. P., & Parrado Moreno, C. A. (2019). Lo que sabemos y no sabemos sobre los sistemas agroforestales tropicales y la provisión de múltiples servicios ecosistémicos. Una revisión. Revista Ecosistemas, 28(3), p. 26–35.

35. Torres, S. G., & Ariza, F. A. P. (2022). Peasant women and food sovereignty: proposals for a better living, the experience of Inza, Cauca (Colombia). Revista de Economia e Sociología Rural, 60(3), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9479.2021.248019

36. Vargas, R. L., Rivas, J. J. N., & Herrera, D. C. (2020). Los huertos urbanos como estrategia de transición urbana hacia la sostenibilidad en la ciudad de Málaga. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles, (86).

37. Zaar , M. (2011). Agricultura urbana: algunas reflexiones sobre su origen e importancia actual. Revista bibliográfica de Geografia y Ciencias Sociales.

38. Zafra Galvis, Orlando (2006) Tipos de Investigación Revista Científica General José María Córdova, 4(4), p. 13-14

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: María Angélica Vargas I, Diego Armando Osorio H, Leonela Narváez G, Verenice Sánchez Castillo.

Data curation: María Angélica Vargas I, Diego Armando Osorio H, Leonela Narváez G, Verenice Sánchez Castillo.

Formal analysis: María Angélica Vargas I, Diego Armando Osorio H, Leonela Narváez G, Verenice Sánchez Castillo.

Research: María Angélica Vargas I, Diego Armando Osorio H, Leonela Narváez G, Verenice Sánchez Castillo.

Writing – original draf: María Angélica Vargas I, Diego Armando Osorio H, Leonela Narváez G, Verenice Sánchez Castillo.

Writing – review and editing: María Angélica Vargas I, Diego Armando Osorio H, Leonela Narváez G, Verenice Sánchez Castillo.