doi: 10.62486/agmu202497

ORIGINAL

Chronic Kidney Disease, Mortality in the Elderly in Cuba

Enfermedad Renal Crónica, Mortalidad en el Adulto Mayor en Cuba

María del

Carmen Marín Prada1 ![]() , Francisco Gutiérrez García2

, Francisco Gutiérrez García2 ![]() , Miguel Ángel Martínez Morales3

, Miguel Ángel Martínez Morales3 ![]() , Jhossmar Cristians Auza-Santivañez4

, Jhossmar Cristians Auza-Santivañez4 ![]() *

*

1Departamento de Investigación y Docencia. Instituto de Nefrología. La Habana, Cuba.

2Instituto de Nefrología “Dr. Abelardo Buch López”. La Habana, Cuba.

3Ministerio de Salud Pública. Dirección Nacional de Estadística. La Habana, Cuba.

4Ministerio de Salud y Deportes. Instituto Académico Científico Quispe-Cornejo. La Paz, Bolivia.

Cite as: Marín Prada M del C, Gutiérrez García F, Martínez Morales MÁ, Auza-Santivañez JC. Chronic Kidney Disease, Mortality in the Elderly in Cuba. Multidisciplinar (Montevideo). 2024; 2:97. https://doi.org/10.62486/agmu202497

Submitted: 20-12-2023 Revised: 07-04-2024 Accepted: 14-08-2024 Published: 15-08-2024

Editor: Telmo

Raúl Aveiro-Róbalo ![]()

ABSTRACT

Introduction: population aging is a global reality. Age is the most important prognostic factor for kidney disease.

Objective: to characterize the mortality of the elderly with chronic kidney disease (CKD) in Cuba, in the period 2011-2019.

Method: cross-sectional descriptive research. The universe corresponded to the 24 181 deceased over 60 years with CKD in Cuba in the period. The information was taken from the mortality database of the Ministry of Public Health. Absolute and relative frequencies, crude rates of mortality, specific and years of life potentially lost were calculated. Mortality was stratified by province of residence.

Results: among the deceased older than 60, males (52 %) and white-skinned subjects (64 %) predominated. The average mortality rate during the period was 12,5 per 10 000 inhabitants (h). The risk of death was higher in those older than 85 years (34,5 x 10 000 h). The highest rates corresponded to the provinces: Artemisa (18,2), Cienfuegos (15,7), Matanzas (14,5) and Havana (14,5). The main cause of death in the subjects studied was hypertensive kidney disease (42,3 per 100 000 h).

Conclusions: there is a slight tendency to increase mortality in the group studied in the country. The risk of death from CKD at the provincial level presents differences; it is higher in the provinces of Artemisa, Cienfuegos, Matanzas and Havana. The main causes of death in individuals with the characteristics studied are hypertensive kidney disease and diabetes mellitus.

Keywords: Mortality; Elderly; Risk of Mortality; Arterial Hypertension; Diabetes Mellitus; Chronic Kidney Disease; Cuba.

RESUMEN

Introducción: el envejecimiento poblacional es una realidad mundial. La edad es el factor pronóstico de mayor peso para las enfermedades renales.

Objetivo: caracterizar la mortalidad del adulto mayor con enfermedad renal crónica (ERC) en Cuba, en el período 2011-2019.

Método: investigación descriptiva transversal. El universo correspondió a los 24 181 fallecidos mayores de 60 años con ERC en Cuba en el período. La información fue tomada de la base de datos de mortalidad del Ministerio de Salud Pública. Se calcularon frecuencias absolutas y relativas, tasas crudas de mortalidad, específicas y años de vida potencialmente perdidos. Se estratificó la mortalidad por provincia de residencia.

Resultados: entre los fallecidos mayores de 60 predominaron los varones (52 %) y los sujetos de piel blanca (64 %). La tasa promedio de mortalidad durante el período fue 12,5 por 10 000 habitantes (h). El riesgo de muerte resultó más elevado en los mayores de 85 años (34,5 x 10 000 h). Las mayores tasas correspondieron a las provincias: Artemisa (18,2), Cienfuegos (15,7), Matanzas (14,5) y La Habana (14,5). La principal causa de muerte de los sujetos estudiados fue la enfermedad renal hipertensiva (42,3 por 100000 h).

Conclusiones: existe ligera tendencia al incremento de la mortalidad del grupo estudiado en el país. El riesgo de muerte por ERC a nivel provincial presenta diferencias; es mayor en las provincias de Artemisa, Cienfuegos, Matanzas y La Habana. Las principales causas de muerte de los individuos con las características estudiadas son enfermedad renal hipertensiva y diabetes mellitus.

Palabras clave: Mortalidad; Adulto Mayor; Riesgo de Mortalidad; Hipertensión Arterial; Diabetes Mellitus; Enfermedad Renal Crónica; Cuba.

INTRODUCTION

Population aging is a global reality; the proportion of older people in the general population is increasing.(1) This demographic change results from socioeconomic development and longer life expectancy in countries.(2) In the US, patients over 65 years of Age have a substantially higher mortality rate compared to the general population.(3,4) Age is one of the variables independently associated with mortality.(5)

Kidney disease has an indirect impact on global morbidity and mortality by increasing the risks associated with at least five other leading causes of death: cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, high blood pressure, human immunodeficiency virus infection, and malaria. The 2015 Global Burden of Disease study estimated that 1,2 million deaths, 19 million disability-adjusted life years, and 18 million potential years of life lost due to cardiovascular disease were directly attributable to reduced glomerular filtration rates.(6,7)

The results of the EPIRCE study (Epidemiology of Chronic Renal Failure in Spain) reveal that kidney disease affects approximately 10 % of the adult population in Spain(8) and more than 20 % of those over 60 years of Age.(9,10) In the US, mortality from CKD in patients aged 65 years or older is twice that of the 44-64 age group and four times higher than in the 20-44 age group. Age is the most important prognostic factor; for every 10-year increase in Age, the risk of mortality increases 1.8-fold.(11,12) As Age increases, more older adults with CKD die.(5)

In Cuba, life expectancy at birth increased 2019 to 78,45 years (men 76,50 and women 80,45).(13) The percentage of older adults in the general population was 17,9 % in 2011 and 20,8 % in 2019, representing a relative increase of 16,2 %.(13) The increase in the incidence and mortality of CKD worldwide and Cuba, together with the aging population,(14,15,16,17,18,19) motivated the development of this research to characterize mortality in older adults with CKD in Cuba from 2011-2019.

METHOD

A descriptive, cross-sectional study was conducted. The study population consisted of 24 181 Cuban deaths over the Age of 60 between 2011 and 2019, in which CKD was listed as one of the causes of death on the death certificate.

The information was obtained from the Mortality Database of the National Directorate of Medical and Statistical Records of the Ministry of Public Health of the Republic of Cuba. The following variables were recorded: year of death, Age, sex, skin color, province of residence, cause of death, occupational category,(20) place of death, and certifying physician.

In operationalizing the variable “occupational category,” the National Office of Statistics and Information job classification was used, and the Tenth International Classification of Diseases was used to define the causes of death.(21) The rates were calculated using the populations corresponding to the 2012 Population and Housing Census and projections from the National Statistics and Information Office for the remaining years.(22)

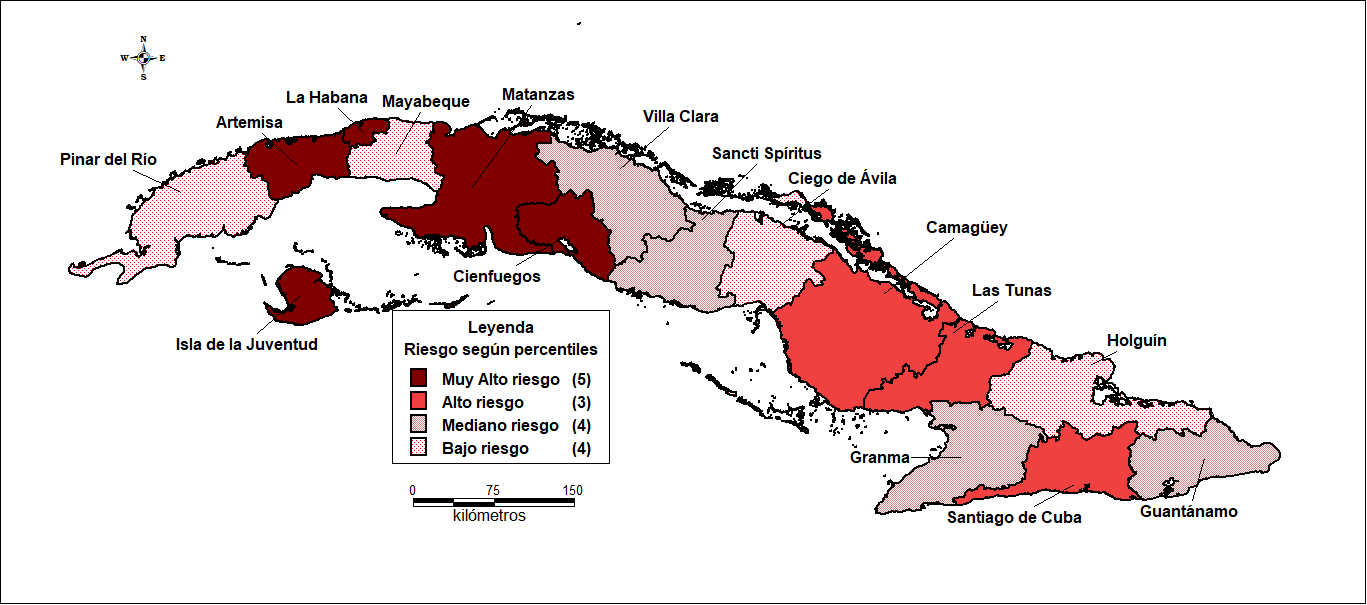

The risk of dying from CKD was stratified using the crude mortality rates of the provinces, based on the quartiles of their distribution, and provinces with rates above 14 were considered to be at very high epidemiological risk 4 x 10 000 inhabitants; high epidemiological risk stratum, those with rates between 14,4 and 12,3 x 10 000 inhabitants; medium risk stratum, those with rates between 12,2 and 9,6 x 10 000 inhabitants; and low-risk stratum, those with rates below 9,6 x 10 000 inhabitants. The free software QGIS, version 3.4, was used to implement the map and use geographic information systems. The digital cartographic base of Cuba was implemented by the province on a scale of 1:25 000.

This research was approved by the Institute of Nephrology’s Scientific Council and Ethics Committee. The study guaranteed the confidentiality of the information.

The data were processed automatically using SPSS version 20.0. Absolute and relative frequencies were calculated, and crude mortality rates and specific mortality rates were calculated by year, age group, sex, province, and cause of death, which were expressed multiplied by a power of 10 n to facilitate interpretation.

RESULTS

In Cuba, 30 706 individuals with CKD died between 2011 and 2019. Of these, 24 181 (78,7 %) belonged to the age group over 60 years. Among the latter, males predominated (52 %), and white individuals constituted 64 %. Black and mixed-race individuals accounted for the same percentage (17 %).

During this period, the average mortality rate for patients over 60 years of age with CKD was 12,5 per 10 000 inhabitants (h). The AVPP for subjects aged 60 to 78 years was 23 040,9; with a rate of 4,6 years per 1 000 h.

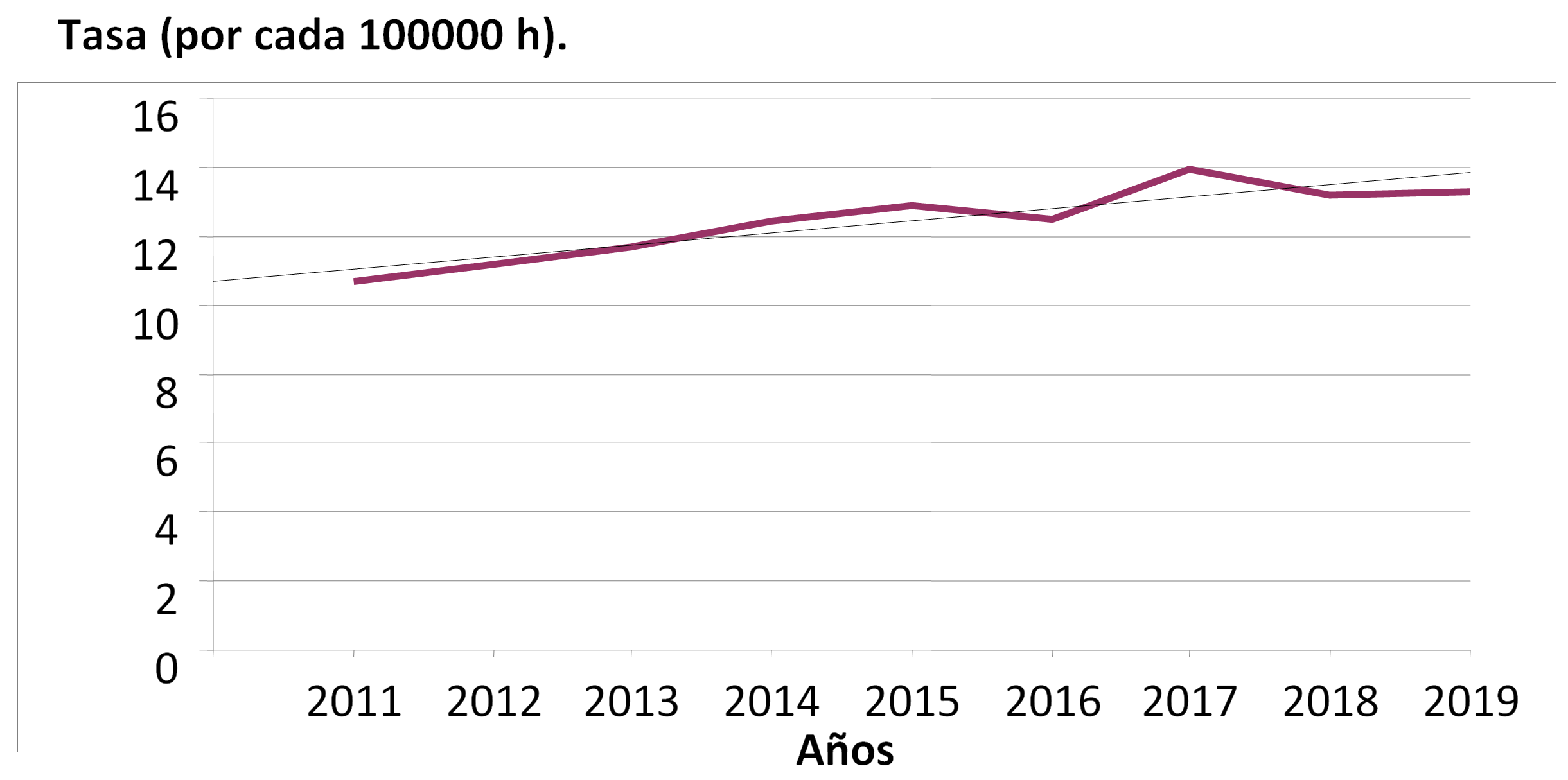

Mortality figures for those over 60 increased from 10,7 per 10 000 inhabitants (h) in 2011 to 13,3 per 10 000 h in 2019. The relative change over the period was 24,3 %. Figure 1 shows a slight but steady increase in rates, with a slight upward trend in mortality in the country in the group studied.

Figure 1. Mortality in individuals over 60 years of age with chronic kidney disease, Cuba 2011-2019. Trend line using the linear regression method

During the study period, the risk of death was higher in men, with a rate of 13,7 per 10 000 males, while in women it was 11,3 per 10 000 females. The rate ratio was 1,16:1. In general, the risk of dying increased with age, although the 70-79 age group had the lowest figures (2,7 per 10 000). The highest risk of dying was in the over-85 age group, with a rate of 34,5 per 10 000, more than five times higher than that of the 60-69 age group (6,4 per 10 000) and more than three times higher than that of the 80-84 age group (10,1 per 10 000) (table 1).

|

Table 1. Mortality in people over 60 with chronic kidney disease by age group. Cuba, 2011–2019. |

||

|

Age (years) |

No. |

Rate* |

|

60-69 |

692 |

6,4 |

|

70-79 |

937 |

2,7 |

|

80-84 |

194 |

10,1 |

|

≥ 85 |

620 |

34,5 |

|

Note: * Per 10 000 inhabitants. |

||

The highest crude mortality rates were in the provinces of Artemisa (18,2), Cienfuegos (15,7), Matanzas (14,5), and Havana (14,5), which are at very high epidemiological risk. The Special Municipality of Isla de la Juventud also had a rate of 18,6; considered a very high epidemiological risk. The provinces with the lowest mortality rates were Las Tunas (14,3), Camagüey (13,6), and Santiago de Cuba (12,5), which are at high epidemiological risk. The provinces of Sancti Spíritus, Villa Clara, Granma, and Guantánamo continued to have medium epidemiological risk, and the provinces of Pinar del Río, Holguín, Ciego de Ávila, and Mayabeque had the lowest rates, with low epidemiological risk (figure 2).

Figure 2. Risk of mortality in people over 60 with chronic kidney disease by province of residence. Cuba, 2011–2019.

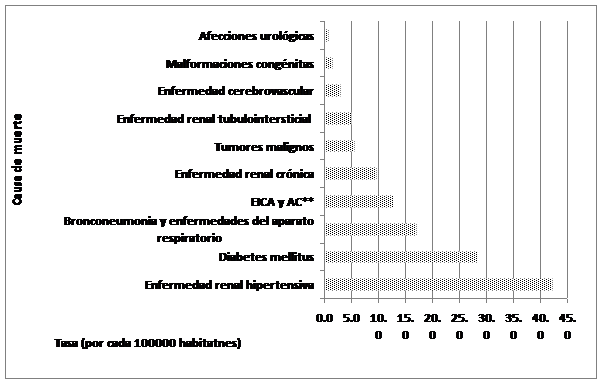

The leading causes of death in people over 60 with chronic kidney disease in the period 2011-2019 were hypertensive kidney disease (HKD) (rate of 42,3 per 100 000 people) and diabetes mellitus (28,3 per 100 000 people). These were followed by bronchopneumonia and respiratory diseases (17,1 per 100 000 h), ischemic heart disease, atherosclerosis, and circulatory diseases (12,8 per 100 000 h), with much lower rates observed in stage 5 chronic kidney disease, malignant tumors, tubulointerstitial kidney disease, cerebrovascular disease, congenital malformations, and urological conditions (figure 3).

Figure 3. Leading causes of death in people over 60 with chronic kidney disease. Cuba, 2011–2019

Eighty-eight percent of deceased patients were retired or pensioners and were male, while 48 % of female deaths were related to domestic work. Two point nine percent of the study subjects were male farmers and fishermen (table 2).

|

Table 2. Deaths over 60 years of age with chronic kidney disease by occupational category and sex. Cuba, 2011-2019 |

||||

|

Occupational category |

Male |

Feminine |

||

|

No |

% |

No |

% |

|

|

Retired |

10119 |

80,9 |

4697 |

40,3 |

|

Pensioners |

869 |

6,9 |

967 |

8,3 |

|

Household chores |

1 |

,0 |

5704 |

48,9 |

|

Not declared working age |

416 |

3,3 |

132 |

1,1 |

|

Farmers and fishermen |

365 |

2,9 |

10 |

0,1 |

|

Unskilled workers |

202 |

1,6 |

36 |

0,3 |

The place of death for more than 60 % of the subjects was a hospital ward, followed by the home (18 %) and, less frequently, the emergency room (10 %). The rest of the patients died elsewhere (table 3). More than 66 % of deaths were certified by the doctor on duty, 12,6 % by the attending physician, and 7,1 % by the family doctor. The rest of the certificates were issued by other physicians.

|

Table 3. Places of death of people over 60 years of age with chronic kidney disease. Cuba, 2011-2019 |

||

|

Age (years) |

No. |

% |

|

Security guard |

3219 |

10,5 |

|

Hospital admission |

19287 |

62,8 |

|

Other medical center |

827 |

2,7 |

|

Home address |

4849 |

15,8 |

|

Other location |

2306 |

7,5 |

|

Unknown |

190 |

0,6 |

DISCUSSION

Kidney disease has risen from the thirteenth leading cause of death worldwide to the tenth. Mortality has increased from 813 000 people in 2000 to 1,3 million in 2019.(23) CKD is largely unknown to the general public. It is one of the diseases that have the most significant direct negative impact on the quality of life of those affected and, indirectly, on family life and the healthcare system itself. In the last decade, it has increased mainly in older age groups.(5)

In Cuba, the mortality rate from CKD in people over 60 showed a slight but steady increase during the period. Still, the increase was significant in Mexico, Spain, and the United States.(16,17,19) This corresponds to the aging of the population worldwide and in Cuba.(3) The Cuban population is classified as one of the oldest in Latin America, with older adults accounting for more than 20 % of the population at the end of 2019. At the same time, the number of people over 60 with CKD is increasing as a result of longer life expectancy.(13) By 2040, chronic kidney disease could become the fifth leading cause of years of life lost worldwide.

The mortality rate was higher in men, which is consistent with national and international studies(14,16,19,25) showing that the relative risk of mortality is higher in men than in women, mainly from cardiovascular causes. Some studies show higher survival rates in women, others mention an increase in mortality in women, and others show no significant differences.(26,27)

In Cuba, 64 % of the general population has white skin color.(20) One of the variables analyzed was skin color; the highest frequency corresponded to white skin color, coinciding with studies conducted in the country.(14,19,25)

The mortality rate was higher in those over 85 years of age; these results are consistent with national and international studies,(12,17,27,28,29) an aspect closely related to the increase in this population group in the country and worldwide. It has been demonstrated that all kidney changes caused by aging affect the kidney’s ability to support and respond to any damage, increasing susceptibility to progressive chronic kidney disease. Various studies have shown that the kidney undergoes histological and functional changes with aging.(30,31,32) After age 70, the average number of sclerotic glomeruli is 10-20 %, but it is common to see percentages greater than 30 % in individuals over 80.(33) Most older adults with CKD experience a progressive clinical deterioration of their general condition until they die from complications related to comorbidities.

The highest risk of death was observed in patients from the provinces of Artemisa, Cienfuegos, Matanzas, Havana, and the municipality of Isla de la Juventud, which coincides with the provinces with the highest prevalence rates of CKD in primary health care, as reported in the Chronic Kidney Disease Registry in Cuba.(34) The provinces with the highest mortality rates are located in the western part of the country. We found no information on this subject in the literature reviewed.

CKD is a significant risk factor for death in patients with diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, and cerebrovascular disease, which are the leading causes of death and disability in older patients.(35) In Cuba, there has been an increase in mortality from the diseases mentioned above in the last five years.(29)

Hypertensive disease and diabetes mellitus were the leading causes of death among those who died with CKD, which is alarming because these diseases are highly prevalent in the population and, as they progress and are not adequately controlled and treated, combined with the kidney damage associated with aging, they result in a worse prognosis, complications, and death. These diseases have increased worldwide in the last ten years, and Cuba is no stranger to this phenomenon.(13)

Diabetes has become one of the 10 leading causes of death worldwide, following a significant 70 % increase since 2000. It is also responsible for the most significant increase in deaths among men, with an 80 % increase since 2000.(23) Mexico and Argentina are examples of this.(35,36)

The category of retirees predominated the study, which is in line with another study conducted in Cuba.(26) The results found could be related to the age group studied, as people over 60 are very close to retirement, and most patients with CKD, due to their condition, have to face multiple stressors that require a process of lifestyle adjustment, during which various psychological and social problems may arise. Depression and anxiety, combined with the loss of immune system function, lead to a deterioration in their quality of life and their decision to enter this category.(37,38)

The occupation of farmers and fishermen, although still low in frequency, showed the highest percentage after retirees. This occupation was more common among men, consistent with another study conducted in the country.(25) The last occupation of the subjects before they fell ill was not known. The research team considers that it would be important in future studies to investigate the occupation of the deceased before they fell ill, to investigate the environmental working conditions, and the possible relationship between occupation and the development of the disease, as other countries have described the association between certain occupations, ecological factors, and mortality.(39,40,41,42)

Most of these patients die in the hospital. The decompensation of various comorbidities and their poor immune status lead to frequent complications, resulting in multiple hospital admissions, a deterioration in their general condition, and ultimately death. More than 66 % of these patients were certified dead by the doctor on duty, a factor that could influence the quality of the death certificate since this doctor is unaware of the patient’s medical history and clinical evolution, among other deficiencies mentioned in studies carried out in the country.(43,44) Another essential tool in identifying the causes of death of these patients is the autopsy, a procedure that represents a significant step forward in the quality of diagnosis and the completion of death certificates, although autopsies have not yet become established in the country.(45)

CONCLUSIONS

There is a slight upward trend in mortality among CKD patients in the over-60 age group in the country. Men over 60 years of age with white skin color are at higher risk of dying from chronic kidney disease. The risk of dying from chronic kidney disease at the provincial level varies during the study period, with higher rates in the provinces of Artemisa, Cienfuegos, Matanzas, Havana, and the municipality of Isla de la Juventud than in the rest of the country. Hypertensive kidney disease and diabetes mellitus are the leading causes of death. The results of this study contribute to the epidemiological update of mortality in people over 60 with CKD in Cuba.

REFERENCES

1. World Health Organization. Good health adds life to years: global brief for World Health Day 2012. WHO: Geneva, 2012.

2. Wiener JM, Tilly J. Population aging in the United States of America: implications for public programmes. Int J Epidemiol 2002; 31: 776-81.

3. Lorenzo V, López Gómez JM (Eds). Enfermedad Renal Crónica. Nefrología al día. https://www.nefrologiaaldia.org/136. Consultado 09 Feb 2021.

4. Saran R, Robinson B, Abbott KC, Agodoa LYC, Bragg-Gresham J, Balkrishnan R, et al. US Renal Data System 2018 Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019 Mar;73(3 Suppl 1):A7-A8.

5. Heras M, Fernández-Reyes MJ, Sánchez R, Guerrero MT, Molina Á, Astrid Rodríguez M. Ancianos con enfermedad renal crónica: ¿qué ocurre a los cinco años de seguimiento? Nefrología 2012;32(3):300-5

6. Kassebaum NJ, Arora M, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Brown J, Carter A, et al.; GBD 2015 DALYs and HALE Collaborators. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 315 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE), 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016 10 8;388(10053):1603–58. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31460-X

7. Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Carter A, et al.; GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016 Oct 8;388(10053):1459–544. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1 pmid: 27733281

8. Otero A, ALM de Francisco, Gayoso P, Garcia F: Prevalencia de la insuficiencia renal crónica en España:Resultados del estudio EPIRCE. Nefrologia 2010;30(1):78-86. DOI: 10.3265/Nefrologia.pre2009.Dic.5732.

9. Lorenzo V. Enfermedad Renal Crónica. En: Lorenzo V, López Gómez JM (Eds). http://www.revistanefrologia.com/es-monografias-nefrologia-dia-articulo-enfermedad-renal-crnica-136.

10. Nefrología al día. Enfermedad Renal Crónica. https://www.nefrologiaaldia.org/136

11. Sarnak MJ. Cardiovascular complications in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003 Jun;41(5 Suppl):11-7. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00372-x. PMID: 1277630911- Joly D, Anglicheau D, Alberti C, Nguyen AT, Touam M, Grünfeld JP, Jungers P. Octogenarians reaching end-stage renal disease: cohort study of decision-making and clinical outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003 Apr;14(4):1012-21. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000054493.04151.80. PMID: 12660336.

12. Perez Escobar MM, Herrera Cruz N, Pérez Escobar E. Comportamiento de la mortalidad del adulto en hemodiálisis crónica. Arch Méd Camagüey. 2017; 21(1):[aprox. 13 p.]. http://revistaamc.sld.cu/index.php/amc/article/view/4579

13- Oficina Nacional de Estadística e Información. Anuarios Estadísticos de salud. Cuba. Año del 2011-2019. http://www.iqb.es/patologia/e20_015.htm

14. Bacallao-Méndez RA, López-Marín L, Llerena-Ferrer B, Gutiérrez-García F, Heras- Mederos A, Cabrera-Eugenio AP. Biopsia renal percutánea en pacientes mayores de 60 años. Análisis clínico-patológico. Nefro Latinoam. 2020;17:25-33. www.nefrologialatinoamericana.com

15. Gorostidi M, Santamaría R, Alcázar R, Fernández-Fresnedo G, Galcerán JM, Goicochea M, et al. Documento de la Sociedad Española de Nefrología sobre las guías KDIGO para la evaluación y el tratamiento de la enfermedad renal crónica. Nefrologia 2014;34(3):302-16 doi:10.3265/Nefrologia.pre2014.Feb.12464

16. Portilla Fanco ME; Tornero Molina F y Gil Gregorio P. La fragilidad en el anciano con enfermedad renal crónica. Nefrología (Madr.) . 2016, vol.36, n.6, pp.609-615. ISSN 1989-2284. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nefro.2016.03.020.

17. Walker SR, Wagner M, Tangri N. Chronic kidney disease, frailty, and unsuccessful aging: a review. J Ren Nutr. 2014 Nov;24(6):364-70. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2014.09.001. Epub 2014 Oct 22. PMID: 25443544.

18. Campbell KH, O’Hare AM. Kidney disease in the elderly: update on recent literature. Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension. 2008 May;17(3):298-303. DOI: 10.1097/mnh.0b013e3282f5dd90. PMID: 18408482.

19. Fiterre Lancis I, Fernández-Vega García S, Rivas Sierra RA, Sabournin Castelnau NL, Castillo Rodriguez B, Gutiérrez García F, López Marín L, et al. Mortalidad en pacientes con enfermedad renal. Instituto de Nefrología. 2016 y 2017. Rev haban cienc méd. 2019;, 18(2):[aprox. 13 p.]. http://www.revhabanera.sld.cu/index.php/rhab/article/view/2520

20. Oficina Nacional de Estadísticas e Información. Clasificador Nacional de Actividades Económicas (CNAE), Enero 2021. 11/02/2021. http://www.onei.gob.cu/publicaciones-tipo/Anuario

21. Organización Mundial de la Salud. Clasificación Internacional de Enfermedades décima revisión (CIE-10) Volumen 2. Edición de 2003. disponible: http://ais.paho.org/classifications/Chapters/pdf/Volume2.pdf

22. Oficina Nacional de Estadísticas e Información. El color de la piel según el Censo de Población y Viviendas de 2012. Febrero 2020. http://www.onei.gob.cu/publicaciones-tipo/Anuario/node/14808

23. World Health Statistics 2019 (in press). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. Las 10 principales causas de defunción en el mundo 2009-2019. 2020. www.who.int/countries

24. Foreman KJ, Marquez N, Dolgert A, Fukutaki K, Fullman N, McGaughey M, et al . Forecasting life expectancy, years of life lost, and all - cause and cause -specific mortality for 250 causes of death: reference and alternative scenarios for 2016 -40 for 195 countries and territories. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):2052-90. https://doi.org//10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31694-5

25. Marín Prada MC, Gutiérrez García F, Martínez Morales MÁ, Rodríguez García CA, Dávalos Iglesias JM. Mortalidad de los enfermos renales crónicos en edad laboral en Cuba. Rev cubana med . 2021 Jun; 60(2): e1530. http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0034-75232021000200010&lng=es

26. Heras Manuel, Fernández-Reyes M. José, Sánchez Rosa, Guerrero M. Teresa, Molina Álvaro, Rodríguez M. Astrid et al . Ancianos con enfermedad renal crónica: ¿qué ocurre a los cinco años de seguimiento?. Nefrología (Madr.) . 2012 [citado 2021 Ago 02] ; 32( 3 ): 300-305. http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0211-69952012000500005&lng=es.

27. Aldrete-Velasco JA, Chiquete E, Rodríguez-García JA, Rincón-Pedrero R, Correa-Rotter R, García-Peña R et al . Mortalidad por enfermedad renal crónica y su relación con la diabetes en México. Med. interna Méx. 2018 Ago; 34(4): 536-550. https://doi.org/10.24245/mim.v34i4.1877

28. Couser WG, Remuzzi G, Mendis S, Tonelli M. The contribution of chronic kidney disease to the global burden of major noncommunicable diseases. Kidney Int. 2011 Dec;80(12):1258-70. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.368. Epub 2011 Oct 12. PMID: 21993585.

29. Martínez R (PAHO/HSD/HA), Ranero VM (CITE, La Habana, Cuba), Vega E (PAHO/HSS/AH) Crecimiento acelerado de la población adulta de 60 años y más de edad: Reto para la salud pública. PAHO. 9 de diciembre de 2020

30. Izquierdo A, Medina-Gómez G. Papel de la lipotoxicidad en el desarrollo de la lesión renal en el síndrome metabólico y el envejecimiento. Dial Traspl. 2012; 33(3):89---96 doi: 10.1016/j.dialis.2011.11.001

31. Gámez Jiménez AM, Montell Hernández OA, Ruano Quintero V, Alfonso de León JA, Hay de la Puente Zoto M. Enfermedad renal crónica en el adulto mayor. Rev. Med. Electrón. 2013 Ago; 35(4): 306-318. http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1684-18242013000400001&lng=es

32. Gómez Carracedo A, Baztan Corte JJ. Métodos de evaluación de la función renal en el paciente anciano: fiabilidad e implicaciones clínicas. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol. 2009;44(5):266–272 doi:10.1016/j.regg.2009.03.016

33. Praga M. Progresión de la insuficiencia renal crónica en el paciente geriátrico. Nefrología. 1997; Vol. 17. Núm. S3.Junio 1997 Páginas 0-72

34. Pérez-Oliva Díaz Jorge Francisco, Almaguer López Miguel, Herrera Valdés Raúl, Martínez Machín Maitte, Martínez Morales Maricela. Registry of Chronic Kidney Disease in Primary Health Care in Cuba, 2017. Rev haban cienc méd . 2018 Dic; 17(6): 1009-1021. http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1729-519X2018000601009&lng=es.

35. Chávez-Gómez NL, Cabello-López A, Gopar-Nieto R, et al. Enfermedad renal crónica en México y su relación con los metales pesados. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2017;55(6):725-734.

36. Marinovich S, Bisigniano L, Hansen Krogh D, Celia E, Tagliafichi V, Rosa Diez G, Fayad A: Registro Argentino de Diálisis Crónica SAN-INCUCAI 2019. Sociedad Argentina de Nefrología e Instituto Nacional Central Único Coordinador de Ablación e Implante. Buenos Aires, Argentina. 2020.

37. Carrillo -Larco RM, Bernabé-Ortiz. A. Mortalidad por enfermedad renal crónica en el Perú: tendencias nacionales 2003-2015. Rev. perú. med. exp. salud publica . 2018 Jul; 35(3): 409-415. http://dx.doi.org/10.17843/rpmesp.2018.353.3633.

38. Vázquez MI. Aspectos Psicosociales del Paciente en Diálisis. En: Lorenzo V, López Gómez JM (Eds). Nefrología al día. Aspectos Psicosociales del Paciente en Diálisis. https://www.nefrologiaaldia.org/276

39. Hurtado-Arestegui A, Plata-Cornejo R, Cornejo A, Mas G, Carbajal L, Sharma S, Swenson ER, Johnson RJ, Pando J. Higher prevalence of unrecognized kidney disease at high altitude. J Nephrol. 2018 Apr;31(2):263-269. doi: 10.1007/s40620-017-0456-0. Epub 2017 Nov 8. PMID: 29119539.

40. Wegman DH, Apelqvist J, Bottai M, Ekstrom U, Garcia -Trabanino R, Glaser J, et al. Intervention to diminish dehydration and kidney damage among sugarcane workers. Scand J Work Environ Health 2018;44(1):16 -24.

41. Valcke M, Levasseur ME, Soares da Silva A, Wesseling C. Pesticide exposures and chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology: an epidemiologic review. Environ Health. 2017 May 23;16(1):49. doi: 10.1186/s12940-017-0254-0. Erratum in: Environ Health. 2017 Jun 20;16(1):67. PMID: 28535811; PMCID: PMC5442867.

42. Ghosh R, Siddarth M, Singh N, Tyagi V, Kare PK, Banerjee BD, Kalra OP, Tripathi AK. Organochlorine pesticide level in patients with chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology and its association with renal function. Environ Health Prev Med. 2017 May 26;22(1):49. doi: 10.1186/s12199-017-0660-5. PMID: 29165145; PMCID: PMC5664840.

43. Verdecia JAI. Calidad del llenado del certificado médico de defunción. Correo Científico Médico. 2013;17(3):1-4.

44. Rodríguez Martín Odalys, Matos Valdivia Yanara, Anchia Alonso Danoris, Betancourt Valladares Miriela. Principales dificultades en el llenado de los certificados de defunción. Rev Cubana Salud Pública . 2012; 38(3): 414-421. http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0864-34662012000300008&lng=es

45. Durruthy Wilson, Odalys, Sifontes Estrada, Miriam, Martínez Varona, Caridad, Olazábal Hernández, Arturo, Del certificado de defunción al protocolo de necropsias: causas básicas de muerte. Archivo Médico de Camagüey . 2011;15(3):542-552. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=211119971011

FINANCING

The authors did not receive funding for the implementation of this study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: María del Carmen Marín Prada.

Research: María del Carmen Marín Prada, Francisco Gutiérrez García.

Methodology: María del Carmen Marín Prada, Francisco Gutiérrez García, Miguel Ángel Martínez Morales.

Visualization: Jhossmar Cristians Auza-Santivañez.

Writing – original draft: María del Carmen Marín Prada, Francisco Gutiérrez García, Miguel Ángel Martínez Morales, Jhossmar Cristians Auza-Santivañez.

Writing – review and editing: María del Carmen Marín Prada, Francisco Gutiérrez García, Miguel Ángel Martínez Morales, Jhossmar Cristians Auza-Santivañez.